Born in the small village of Chiaravalle, Italy, on 31 August 1870, Maria Montessori entered a world ripe for change.

At the time of her birth, the many individual principalities of Italy, recognising their vulnerability on the European stage, banded together into one united nation. Maria Montessori’s father, Alessandro Montessori, was a civil servant. Her mother, Renilde Stoppani, was a cultured woman. She supported her husband as he moved from place to place, rising in his role as accountant in the new economy. Renilde Stoppani was also a strong-minded individual who encouraged and supported her daughter in achieving whatever her heart and mind desired.

In her early days, Maria Montessori was not an exceptional student, but she did benefit from participation in the educational system that existed in Rome. She readily mastered the required elements of knowledge, but found herself more empowered to study, on her own, those elements of natural science that most captivated her interest. She was not satisfied to just memorise what the teachers presented, but endeavoured to go beyond in order to understand the concepts more fully. This love of the natural sciences automatically led Maria Montessori to a desire to study medicine—the human science.

Despite the strenuous objections of her father and the anti-social limitations regarding the role of women, Maria Montessori entered the University of Rome in 1890 as a student in what today we would call “pre-med”. At age 22, she qualified for entrance to the formal study of medicine, beginning the first formal step in building her professional life.

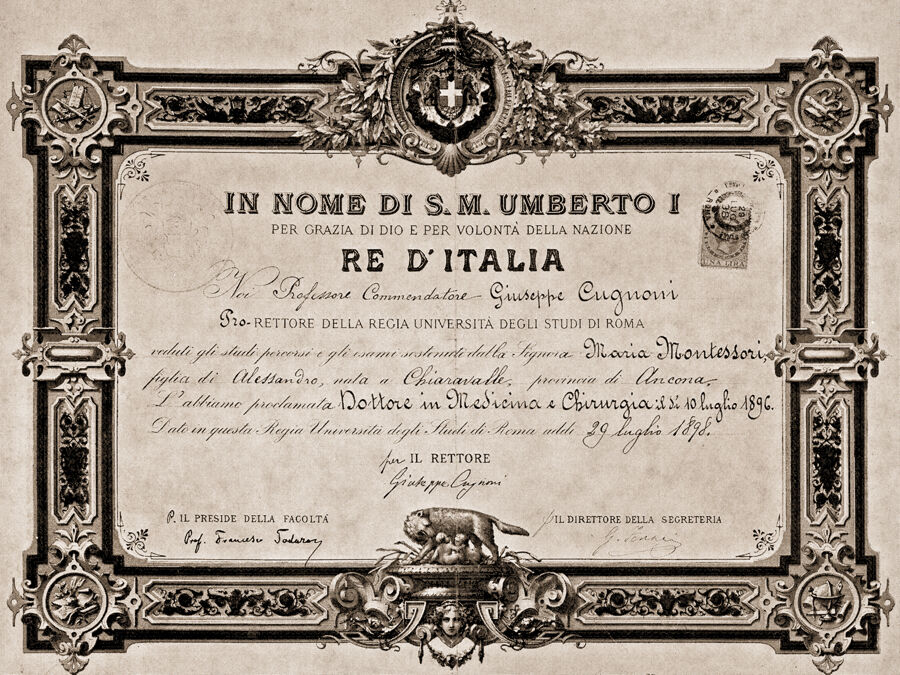

At the Children’s Hospital, Montessori worked in both the consulting room, evaluating and diagnosing children’s illnesses, and in the emergency room. She received the degree Doctor of Medicine in 1896, graduating with the highest honours.

By this time, Montessori had already been recognised in the Italian press for her accomplishments as a parallel influence began to shape her life: Maria Montessori found herself drawn to the dire social issues related to the rights of women and children as her experiences in school and work led her to have strong convictions regarding the cause of the disadvantaged.

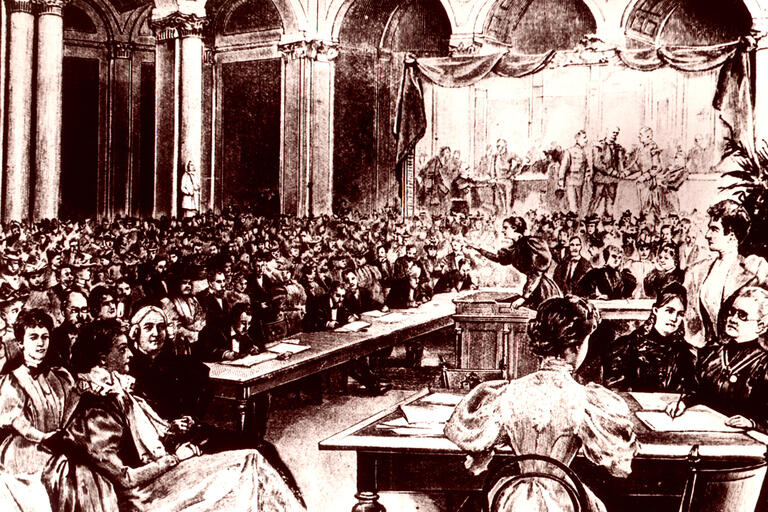

Maria Montessori was surrounded by other influential Italian women and moved in a circle of young liberal activists. Just a short month after her graduation, she was invited to participate as a delegate at a Women’s Conference in Berlin. Her destiny was about to unfold. Delegates came from throughout Europe and Asia, many already well known for their work in the field of women’s rights. But it was the young Maria Montessori who made the greatest impression, both in the press and among her fellow delegates.

As she addressed the assembly, she spoke of the widespread injustice toward women. Press representatives from many countries wrote of her enthusiasm, her presence and her eloquence. They were drawn to her intelligence and her charm. Certainly, an international reputation had been sparked. However, Maria Montessori did not want to be known for either her elegance or her charm. She wanted to be known for the seriousness of her work. She left Berlin determined to make her mark upon the world. Her commitment to the cause of children became a guiding light.

“At birth, the child has to make an enormous effort to adapt. It is the birth of a spirit with mysterious potentialities, of a being who must adapt himself to the environment.”

Maria Montessori, The 1946 London Lectures, p. 109